[1] משירי ארץ אהבתי

מכורה שלי, ארץ נוי אביונה -

למלכה אין בית, למלך אין כתר.

ושבעה ימים אביב בשנה

וסגריר וגשמים כל היתר.

אך שבעה ימים הורדים פורחים,

ושבעה ימים הטללים זורחים,

ושבעה ימים חלונות פתוחים,

וכל קבצנייך עומדים ברחוב

ונושאים חיוורונם אל האור הטוב,

וכל קבצנייך שמחים.

מכורה שלי, ארץ נוי אביונה,

למלכה אין בית למלך אין כתר.

רק שבעה ימים חגים בשנה

ועמל ורעב כל היתר.

אך שבעה ימים הנרות ברוכים

ושבעה ימים שולחנות ערוכים,

ושבעה ימים הלבבות פתוחים,

וכל קבצנייך עומדים בתפילה,

ובנייך בנותייך חתן כלה,

וכל קבצנייך אחים.

עלובה שלי, אביונה ומרה,

למלך אין בית, למלכה אין כתר -

רק אחת בעולם את שבחך אמרה

וגנותך חרפתך כל היתר.

ועל כן אלך לכל רחוב ופינה,

לכל שוק וחצר וסמטה וגינה,

מחורבן חומתייך כל אבן קטנה -

אלקט ואשמור למזכרת.

ומעיר לעיר, ממדינה למדינה

אנודה עם שיר ותיבת נגינה

לתנות דלותך הזוהרת.

מכורה שלי, ארץ נוי אביונה -

למלכה אין בית, למלך אין כתר.

ושבעה ימים אביב בשנה

וסגריר וגשמים כל היתר.

אך שבעה ימים הורדים פורחים,

ושבעה ימים הטללים זורחים,

ושבעה ימים חלונות פתוחים,

וכל קבצנייך עומדים ברחוב

ונושאים חיוורונם אל האור הטוב,

וכל קבצנייך שמחים.

מכורה שלי, ארץ נוי אביונה,

למלכה אין בית למלך אין כתר.

רק שבעה ימים חגים בשנה

ועמל ורעב כל היתר.

אך שבעה ימים הנרות ברוכים

ושבעה ימים שולחנות ערוכים,

ושבעה ימים הלבבות פתוחים,

וכל קבצנייך עומדים בתפילה,

ובנייך בנותייך חתן כלה,

וכל קבצנייך אחים.

עלובה שלי, אביונה ומרה,

למלך אין בית, למלכה אין כתר -

רק אחת בעולם את שבחך אמרה

וגנותך חרפתך כל היתר.

ועל כן אלך לכל רחוב ופינה,

לכל שוק וחצר וסמטה וגינה,

מחורבן חומתייך כל אבן קטנה -

אלקט ואשמור למזכרת.

ומעיר לעיר, ממדינה למדינה

אנודה עם שיר ותיבת נגינה

לתנות דלותך הזוהרת.

[1] Mishirei Eretz Ahavati

Mechorah sheli, eretz noi evyonah -

lamalkah ein bayit, lamelech ein keter.

Veshiv'ah yamim aviv bashanah

vesag'rir ug'shamim kol hayeter.

Ach shiv'ah yamim hav'radim por'chim,

veshiv'ah yamim hat'lalim zor'chim,

veshiv'ah yamim chalonot p'tuchim,

vechol kab'tzanaich omdim barechov

venos'im chivronam el ha'or hatov,

vechol kab'tzanaich s'mechim.

Mechorah sheli, eretz noi evyonah,

lamalkah ein bayit, lamelech ein keter.

rak shiv'ah yamim chagim bashanah

ve'amal vera'av kol hayeter.

Ach shiv'ah yamim hanerot b'ruchim

veshiv'ah yamim shulchanot aruchim,

veshiv'ah yamim halevavot p'tuchim,

vechol kab'tzanaich omdim bit'filah,

uvanaich b'notaich chatan kalah,

vechol kab'tzanaich achim.

Aluvah sheli, evyonah umarah,

lamelech ein bayit, lamalkah ein keter -

rak achat ba'olam et shiv'chech amrah

ug'nutech cherpatech kol hayeter.

Ve'al ken elech lechol rechov ufinah,

lechol shuk vechatzer vesimtah veginah,

mechurban chomotaich kol even k'tanah -

alaket ve'eshmor lemazkeret.

Ume'ir le'ir, mim'dinah lim'dinah

anudah im shir veteivat neginah

letanot dalutech hazoheret.

Mechorah sheli, eretz noi evyonah -

lamalkah ein bayit, lamelech ein keter.

Veshiv'ah yamim aviv bashanah

vesag'rir ug'shamim kol hayeter.

Ach shiv'ah yamim hav'radim por'chim,

veshiv'ah yamim hat'lalim zor'chim,

veshiv'ah yamim chalonot p'tuchim,

vechol kab'tzanaich omdim barechov

venos'im chivronam el ha'or hatov,

vechol kab'tzanaich s'mechim.

Mechorah sheli, eretz noi evyonah,

lamalkah ein bayit, lamelech ein keter.

rak shiv'ah yamim chagim bashanah

ve'amal vera'av kol hayeter.

Ach shiv'ah yamim hanerot b'ruchim

veshiv'ah yamim shulchanot aruchim,

veshiv'ah yamim halevavot p'tuchim,

vechol kab'tzanaich omdim bit'filah,

uvanaich b'notaich chatan kalah,

vechol kab'tzanaich achim.

Aluvah sheli, evyonah umarah,

lamelech ein bayit, lamalkah ein keter -

rak achat ba'olam et shiv'chech amrah

ug'nutech cherpatech kol hayeter.

Ve'al ken elech lechol rechov ufinah,

lechol shuk vechatzer vesimtah veginah,

mechurban chomotaich kol even k'tanah -

alaket ve'eshmor lemazkeret.

Ume'ir le'ir, mim'dinah lim'dinah

anudah im shir veteivat neginah

letanot dalutech hazoheret.

Contributed by Riccardo Gullotta - 2020/3/30 - 16:07

Language: English

ענגליש איבערזעצונג / English translation / Traduzione inglese / Traduction anglaise / Englanninkielinen käännös:

hebrewsongs

hebrewsongs

FROM THE SONGS OF MY BELOVED LAND

My homeland - land of beauty and poverty.

The queen has no home, the king has no crown.

There are seven spring days in the year

And cold and rain all the rest.

But for seven days the roses bloom,

And for seven days the dew drops shine,

And for seven days, windows are open.

And all your poor folk stand in the street

And lift their pale faces toward the good light,

And all your poor folk are happy.

My homeland, land of beauty and poverty,

The queen has no home, the king has no crown.

There are seven holy days in the year

And hunger and toil all the rest.

But for seven days the candles are blessed,

And for seven days the tables are set,

And for seven days, hearts are open.

And all your poor folk stand in prayer,

Your sons and daughters are grooms and brides,

And all your poor folk are brethren.

My miserable land, impoverished and bitter,

The king has no home, the queen has no crown.

Only one in the world your praises has spoken;

Your infamy and shame all the rest.

And therefore I’ll visit every street and corner,

Every market and courtyard and alley and garden.

From the rubble of your ruins I’ll gather little stones

To keep for souvenirs.

As from town to town, from country to country,

I’ll wander with a song and a music box

To relate your glorious penury.

My homeland - land of beauty and poverty.

The queen has no home, the king has no crown.

There are seven spring days in the year

And cold and rain all the rest.

But for seven days the roses bloom,

And for seven days the dew drops shine,

And for seven days, windows are open.

And all your poor folk stand in the street

And lift their pale faces toward the good light,

And all your poor folk are happy.

My homeland, land of beauty and poverty,

The queen has no home, the king has no crown.

There are seven holy days in the year

And hunger and toil all the rest.

But for seven days the candles are blessed,

And for seven days the tables are set,

And for seven days, hearts are open.

And all your poor folk stand in prayer,

Your sons and daughters are grooms and brides,

And all your poor folk are brethren.

My miserable land, impoverished and bitter,

The king has no home, the queen has no crown.

Only one in the world your praises has spoken;

Your infamy and shame all the rest.

And therefore I’ll visit every street and corner,

Every market and courtyard and alley and garden.

From the rubble of your ruins I’ll gather little stones

To keep for souvenirs.

As from town to town, from country to country,

I’ll wander with a song and a music box

To relate your glorious penury.

Contributed by Riccardo Gullotta - 2020/3/30 - 16:16

Language: Italian

תרגום לאיטלקית / Traduzione italiana / Italian translation / Traduction italienne / Italiankielinen käännös:

Riccardo Gullotta

Riccardo Gullotta

DALLE CANZONI DELLA MIA AMATA TERRA

La mia terra- terra di bellezza e povertà.

La regina non ha dimora, il re non ha corona.[1]

In un anno sette giorni di primavera

e freddo e pioggia per il resto dell’anno.

Ma per sette giorni le rose sbocciano,

e per sette giorni le goccie di rugiada brillano,

e per sette giorni le finestre sono aperte.

E tutta la tua povera gente sta nelle strade

E alzano i loro volti pallidi verso la bella luce,

E tutta la tua povera gente è contenta.

La mia terra- terra di bellezza e povertà.

La regina non ha dimora, il re non ha corona.

In un anno sette giorni santi

e fame e fatica per il resto dell’anno.

Ma per sette giorni le candele sono benedette,

e per sette giorni le tavole sono imbandite,

e per sette giorni i cuori si aprono.

E tutta la tua povera gente sta in preghiera,

Figli e figlie sono sposi e spose

E tutti tra la tua povera gente sono fratelli.[2]

La mia terra infelice, resa povera e amara,

Il re non ha dimora, la regina non ha corona.[3]

Soltanto uno al mondo hai detto nelle tue lodi;

ignominia e vergogna per tutto il resto.

Perciò visiterò ogni angolo di strada,

ogni mercato e cortile e viale e giardino.[4]

Dalle macerie dei tuoi ruderi prenderò dei sassolini

Per ricordo.

Di città in città, da paese in paese,

girerò con una canzone e con un carillon

per raccontare la tua miseria e nobiltà.

La mia terra- terra di bellezza e povertà.

La regina non ha dimora, il re non ha corona.[1]

In un anno sette giorni di primavera

e freddo e pioggia per il resto dell’anno.

Ma per sette giorni le rose sbocciano,

e per sette giorni le goccie di rugiada brillano,

e per sette giorni le finestre sono aperte.

E tutta la tua povera gente sta nelle strade

E alzano i loro volti pallidi verso la bella luce,

E tutta la tua povera gente è contenta.

La mia terra- terra di bellezza e povertà.

La regina non ha dimora, il re non ha corona.

In un anno sette giorni santi

e fame e fatica per il resto dell’anno.

Ma per sette giorni le candele sono benedette,

e per sette giorni le tavole sono imbandite,

e per sette giorni i cuori si aprono.

E tutta la tua povera gente sta in preghiera,

Figli e figlie sono sposi e spose

E tutti tra la tua povera gente sono fratelli.[2]

La mia terra infelice, resa povera e amara,

Il re non ha dimora, la regina non ha corona.[3]

Soltanto uno al mondo hai detto nelle tue lodi;

ignominia e vergogna per tutto il resto.

Perciò visiterò ogni angolo di strada,

ogni mercato e cortile e viale e giardino.[4]

Dalle macerie dei tuoi ruderi prenderò dei sassolini

Per ricordo.

Di città in città, da paese in paese,

girerò con una canzone e con un carillon

per raccontare la tua miseria e nobiltà.

La terra a cui la poesia fa riferimento non è Israele ma la Lituania. Anche questa poesia è densa di significati simbolici, nonostante l’apparente semplicità e scorrevolezza. Osserva Vivian Eden che Living creatures and plants in Goldberg's poetry are never simply naturalistically observed; they always carry symbolic, intertextual and metaphorical kit-bags.

[1] Ad esempio nelle immagini del re si intravede il riferimento ai Salmi di Davide e al Deuteronomio.

[2] Un altro tema ricorrente nell’opera di Lea Goldberg . In שארית החיים / The remains of Life (dalla raccolta postuma On the surface of silence) : "We were very young / and very poor / our lives a patchwork. / We read books / and in the evening we went dancing ... / and sometimes we were even happy.

[3] Suggestioni analoghe nella poesia הסתכלות בדבורה / Guardando un’ape ,alla seconda strofa: Come facciamo ad incoronarla // con le parole di una poesia ?// Che possiamo cantare?//Un bambino ci verrà a dire://La regina è nuda.

[4] Quello del paesaggio urbano è un tema caro a Lea Goldberg, dalle prime poesie. Il paesaggio urbano sembra prevalere sulla campagna e le sue connessioni. Nella Terra promessa, futuro stato di Israele, campagna significava kibbutzim e ideali sottesi di associazionismo, di socialismo e di etica sionista.

[Riccardo Gullotta]

[1] Ad esempio nelle immagini del re si intravede il riferimento ai Salmi di Davide e al Deuteronomio.

[2] Un altro tema ricorrente nell’opera di Lea Goldberg . In שארית החיים / The remains of Life (dalla raccolta postuma On the surface of silence) : "We were very young / and very poor / our lives a patchwork. / We read books / and in the evening we went dancing ... / and sometimes we were even happy.

[3] Suggestioni analoghe nella poesia הסתכלות בדבורה / Guardando un’ape ,alla seconda strofa: Come facciamo ad incoronarla // con le parole di una poesia ?// Che possiamo cantare?//Un bambino ci verrà a dire://La regina è nuda.

[4] Quello del paesaggio urbano è un tema caro a Lea Goldberg, dalle prime poesie. Il paesaggio urbano sembra prevalere sulla campagna e le sue connessioni. Nella Terra promessa, futuro stato di Israele, campagna significava kibbutzim e ideali sottesi di associazionismo, di socialismo e di etica sionista.

[Riccardo Gullotta]

Contributed by Riccardo Gullotta - 2020/3/30 - 16:23

Language: Spanish

תרגום ספרדי / Traducción Española / Traduzione spagnola / Spanish translation /Traduction espagnole /Espanjankielinen käännös:

Fernando Sabido Sanchez

Fernando Sabido Sanchez

CANTOS A MI TIERRA QUE AMO

Patria mía, tierra bella y pobre,

la reina no tiene casa y el rey no tiene corona.

y siete días de primavera en el año

y viento y lluvia todos los demás.

Mas en los siete días florecen las rosas,

en los siete días brillan los rocíos,

y en los siete días las ventanas están abiertas,

y todos los mendigos están en la calle

y muestran su palidez a la buena luz,

y todos los mendigos se regocijan.

Patria mía, tierra bella y pobre,

la reina no tiene casa y el rey no tiene corona,

sólo siete días de fiesta en el año,

trabajo y esfuerzo en todos los demás.

Mas siete días bendicen los cirios,

y siete días las mesas servidas,

y siete días los corazones abiertos,

y todos los mendigos están de plegaria,

e hijos e hijas, novios y desposadas,

y todos tus mendigos como hermanos.

Desdichada mía, pobre y amarga,

el rey no tiene casa y la reina no tiene corona,

sólo una vez habló el mundo en tu favor,

oprobio y vergüenza, todas las demás.

Andaré por caminos y esquinas,

por mercados, patios, callejones y parques.

De la destrucción de tus muros, cada guijarro

juntaré y cuidaré como recuerdo.

y de ciudad en ciudad, de país en país,

vagaré con mi canto y caja de música

para contar tu pobreza radiante.

Patria mía, tierra bella y pobre,

la reina no tiene casa y el rey no tiene corona.

y siete días de primavera en el año

y viento y lluvia todos los demás.

Mas en los siete días florecen las rosas,

en los siete días brillan los rocíos,

y en los siete días las ventanas están abiertas,

y todos los mendigos están en la calle

y muestran su palidez a la buena luz,

y todos los mendigos se regocijan.

Patria mía, tierra bella y pobre,

la reina no tiene casa y el rey no tiene corona,

sólo siete días de fiesta en el año,

trabajo y esfuerzo en todos los demás.

Mas siete días bendicen los cirios,

y siete días las mesas servidas,

y siete días los corazones abiertos,

y todos los mendigos están de plegaria,

e hijos e hijas, novios y desposadas,

y todos tus mendigos como hermanos.

Desdichada mía, pobre y amarga,

el rey no tiene casa y la reina no tiene corona,

sólo una vez habló el mundo en tu favor,

oprobio y vergüenza, todas las demás.

Andaré por caminos y esquinas,

por mercados, patios, callejones y parques.

De la destrucción de tus muros, cada guijarro

juntaré y cuidaré como recuerdo.

y de ciudad en ciudad, de país en país,

vagaré con mi canto y caja de música

para contar tu pobreza radiante.

Contributed by Riccardo Gullotta - 2020/3/30 - 16:27

×

![]()

Note for non-Italian users: Sorry, though the interface of this website is translated into English, most commentaries and biographies are in Italian and/or in other languages like French, German, Spanish, Russian etc.

Mishirei Eretz Ahavati

שירה / Poesia / A Poem by / Poésie / Runo:

לאה גולדברג /Lea Goldberg

לחן / Musica / Music / Musique / Sävel:

דפנה אילת / Dafna Eilat

מבוצע על ידי / Interpreti / Performed by / Interprétée par / Laulavat :

1.Chava Alberstein

אלבום / Album : משירי ארץ אהבתי / Songs of my beloved country

2. שרית חדד [ Sarit Hadad]

3. אורה זיטנר [Ora Zitner]

4. רזי בן-עזר [Razi Ben-Ezzer]

5. שרית וינו [Sarit Vino]

Lea Goldberg [ לאה גולדברג ] (Königsberg, 29 maggio 1911 – Gerusalemme, 15 gennaio 1970) è stata una poetessa, traduttrice e scrittrice israeliana in ebraico.

Nata in una famiglia ebrea lituana a Königsberg, all’epoca in Prussia Orientale, oggi in Russia, Lea Goldberg trascorre l’infanzia a Kovno (Kaunas), in Lituania e a Saratov in Russia. Ritornata in Lituania dopo gli anni della Prima guerra mondiale, si diploma al Ginnasio ebraico di Kovno nel 1928 e prosegue gli studi all’università lituana in Semitistica e tedesco, poi a Berlino e infine a Bonn, dove consegue il dottorato in studi semitici sul Targum Samaritano del Pentateuco nel 1933. Diventa allora professoressa di letteratura a Raseiniai, ma nel 1935 decide di emigrare nella Palestina del Mandato britannico. A Tel Aviv Lea lavora come consulente letterario del teatro nazionale Habima e come redattrice per Hapoalim Sifriat / Biblioteca dei lavoratori. Aderisce al gruppo Yachdav, insieme ai poeti Nathan Altermann e Avraham Shlonski , la scuola modernista di cui Shlonski era capofila e a cui tuttavia Lea partecipa in modo originale e personale. Il ‘moderno’ per lei infatti non si pone in contrapposizione al ‘tradizionale’ o al ‘classico’, e il passato è sempre costantemente ‘presente’, non in semplice qualità di risorsa tematica, culturale, o come memoria, ma come fonte inesauribile di vita, di fecondità e di ricchezza. È a Tel Aviv che pubblica la sua prima raccolta di poesie, in ebraico, Anelli di fumo.

Dal 1927 Lea Goldberg aveva abbandonato il russo come lingua della poesia in cui aveva scritto i primi versi e aveva adottato l’ebraico, che tuttavia non considerava come la lingua ‘sacra’ della rivelazione divina, ma come lingua ‘moderna’, viva, al pari delle altre, capace di esprimere tutta la gamma dei sentimenti, anche di contraddizione, dolore e nostalgia, personali e collettivi e la sua visione del mondo. La sua poesia – come la lingua – è infatti permeata dalla poesia europea classica e moderna: i simbolisti russi, prima di tutto, Aleksandr Blok e Osip Madel’štam, i drammi di Ibsen , che traduce, e poi la poesia italiana, che conosce bene e traduce, come Petrarca e Dante, fondendosi a un registro biblico che non fornisce semplici immagini di repertorio, ma originali connessioni alla contemporaneità [….]

La profonda e lucida coscienza della ‘molteplicità’ delle tradizioni, delle culture cui sente di appartenere, è certo un tema chiave della sua produzione e della sua attività intellettuale, così come il dialogo costante fra il passato – e la memoria – e il presente[….]

Nel 1954 si trasferisce a Gerusalemme e inizia a tenere corsi di letteratura all’Università Ebraica, diventa una delle promotrici della letteratura comparata come disciplina accademica in Israele e contribuisce alla costituzione del Dipartimento di Letteratura Comparata di cui è direttrice dal 1963 alla morte.

Ha pubblicato, fra le altre, le raccolte di versi: Spiga dall’occhio verde (1940), Poesia nei villaggi (1942) Della mia vecchia casa (1944) Sulla fioritura (1948; premio «Ruppin» 1949 e «Israele» 1970), Fulmine al mattino (1955), Questa notte (1964) e il volume postumo I resti di una vita (1978, a cura di Tuvia Reubner). Molte delle sue poesie sono state musicate da Alex Wasserman, Yonatan Niv, Noa (Achinoam Nini), Galia Shargal.

[Annalisa Comes]

Una lettura di Lea Goldberg

Lea Goldberg é annoverata tra i più grandi poeti del Novecento. In vita non ebbe grandi riconoscimenti, né in Israele, dove la sua attenzione per la cultura europea si sovrappose a quella per la nuova realtà israeliana suscitando indifferenza se non diffidenza, né all’estero nonostante i contatti e la sua profonda conoscenze delle letterature straniere. A lei va il merito di avere tradotto in ebraico, tra le tante, le opere di Shakespeare, Tolstoj, Mann, Petrarca e Dante. Soltanto in tempi relativamente recenti la sua opera ha ottenuto ampi riconoscimenti in Israele, negli Stati Uniti e in Italia. Fu un’intellettuale molto attiva. Ancora oggi qualcuno ricorda le sue lezioni avvincenti di letteratura comparata alla Università Ebraica di Gerusalemme, le aule gremite, la sua voce resa roca dal fumo delle sigarette.

Agli inizi Lea Goldberg fu influenzata dai simbolisti francesi e dall’acmeismo russo. Da quest’ultimo trasse la propensione alla nitidezza espressiva e al rigore stilistico. Condivise tale approccio in seno al movimento di avanguardia Yachdev / Moderna di cui fecero parte i poeti israeliani Alterman e Shlonsky. Lea Goldberg non fu la prima poetessa ebraica nel secolo scorso. Nel Mandatory Palestine, non ancora stato di Israele, erano note le espressioni artistiche di Raḥel (Rachel Blovstein), Esther Raab , Yocheved Bat-Miriam (Yocheved Zhlezniak), Elishéva (Elizaveta Ivanovna Zhirkov).

Il movimento noto come gruppo Yachdev volle staccarsi dalla poetica romantica di Bialik, acclamato come poeta nazionale di Israele. La Goldberg mantenne sempre una sua identità discosta sia dalla poesia “politica” di Alterman, sionista della prima ora (e anche dell’ultima) sia dalle inflessioni ideologiche di Avraham Shlonsky, pioniere e indefesso costruttore delle basi intellettuali del mondo nuovo. Con l’editore Shlonsky peraltro la Goldberg collaborò molto.

Lea Goldberg dopo la sua morte è stata riconsiderata ; alcune sue opere sono state pubblicate postume.

Una recensione intrigante, è quella di Vivian Eden ,scrittrice, docente di Letteratura comparata e parte della redazione di Haaretz. Ci dice in buona sostanza che la cifra della Goldberg è il Limbo, una no-man’s land di chi non può o non si decide a scegliere una cultura ancorata ad un territorio. Peccato però che la Eden scorge nel limbo un topos di Milton, il Paradiso degli stolti.

Passi per il limbo, ma l’accostamento a quella farsa di paradiso dove Milton aveva relegato personaggi non certo commendevoli ci lascia un che di amaro in bocca. E' un'annotazione che ci sembra fuori posto in un'analisi che ha lasciato il segno nel mondo della critica letteraria.

Dalle poesie che abbiamo potuto leggere, la Goldberg appare come una grande figura di frontiera: è ebrea ed israeliana senza riserve, ma non dimentica ciò che sta da un’altra parte del tempo e dello spazio. Uno degli aspetti che contribuisce alla sua singolare grandezza sta nel non avere eletto la nostalgia a misura delle sue lacerazioni ma di avere trasfigurato un universo cancellato dalla storia e purtuttavia sempre presente. Una voce (non l’unica) in libera uscita dal coro degli intellettuali mobilitati per Eretz Israel.

La terza strofa della poesia “Il pino” [da ברק בא-בוקר / Lightening in the morning ] ci dà una sensazione nitida del dramma che visse nell’intera vita e che traspose senza soluzione di continuità nelle sue poesie:

אוּלַי רַק צִפֳּרֵי-מַסָּע יוֹדְעוֹת –

כְּשֶׁהֵן תְּלוּיוֹת בֵּין אֶרֶץ וְשָׁמַיִם –

אֶת זֶה הַכְּאֵב שֶׁל שְׁתֵּי הַמוֹלָדוֹת.

Forse solo gli uccelli migratori conoscono

- Quando sono sospesi tra terra e cielo-

Il dolore di avere due patrie.

E se a qualcuno tanto non fosse ragione sufficiente per spostarla definitivamente dal limbo, si propongono sei versi che dovrebbero valere più di tante argomentazioni:

da Il lamento di Ulisse [ קינת אודיסיאוס / The lament of Odysseus, Selected Poetry and Drama]

Cento volte più solo è il vivo fra i morti.

A chiedere il vostro perdono nello Sheol io sono disceso

perché lacera, squarciata è la rete - e noi gli scampati.

Sulla mia fronte segno d’infamia la morte del compagno.

Sulla mia fronte segno d'infamia la vita che ho da vivere.

Ci sembra di avere dato qualche indicazione , quanto basta per stimolare l’interesse verso un’artista che meriterebbe più attenzione. In rete si trovano alcune poesie tradotte in italiano e parecchie in inglese.

A chi volesse approfondire temi ed estetica della poesia di Lea Goldberg si suggeriscono due saggi di agevole lettura. Il primo : Francesco Bianchi , Fra il mare e il cielo: Tel Aviv e Gerusalemme nella poesia di Lea Goldberg in “Orientalia Parthenopea, 2014”.Il secondo: Luna Sarti, Echi di Russia nella poesia israeliana in “Innesti e ibridazione tra spazi culturali”,2015.

La musica e le interpretazioni

La composizione della musica è di Dafna Eilat, israeliana sabra. L’interpretazione più nota è quella di Chava Alberstein. Anche se sono trascorsi cinquant’anni dalla prima incisione la sua esecuzione rimane avvincente e, a nostro avviso, quella che meglio è riuscita a calarsi nel mondo della poetessa. E se ne comprende facilmente il motivo: sia la compositrice che Chava vivono la cultura ebraica dell’Europa orientale, come la Goldberg , che morì nel 1970 , qualche mese prima che fosse pubblicato l’album.

Le interpretazioni successive di questa canzone ci offrono uno spaccato della società israeliana. La canzone fu riproposta alle celebrazioni del 70° anniversario della fondazione di Israele, il 18 Aprile 2018 a Gerusalemme. L’interprete era la pop star israeliana Sarit Hadad. L’articolo dell’opinionista Matti Friedman è talmente ficcante che se ne riportano alcuni passi. È’ un’occasione rara per cogliere certe tendenze della musica pop israeliana e altro, come il titolo promette (e mantiene)

The song is an expression of Israel’s founding generation, orphaned children of eastern Europe. That was the song’s spirit when it became a mainstream hit in 1970 as performed by the singer Hava Alberstein, who’d come to Israel as a child from Poland.

But the singer in a shiny white gown who belted out a cover for a national TV audience was Sarit Hadad, one of Israel’s biggest pop stars and the queen of a genre called “Mizrahi,” or “eastern.” In the hands of Ms. Hadad, who has the style and vocal power of the great divas of the Arab world, and with the addition of instruments such as the oud, the poet’s words were transformed into a song of the Middle East.

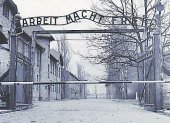

Ms. Hadad’s reinterpretation of Beloved Land drew more attention here than you might expect, because it was understood to be more significant than just a song. Israel tends to think of itself as a Western country, and still explains itself with stories about Europe: the dreams of the Vienna visionary Theodor Herzl, the socialist communes of the kibbutz movement, the Holocaust. But the country was founded in the Middle East, not in Europe, and about half of the Jews in Israel have roots not in Europe but in the Islamic countries of the Middle East and North Africa, in cities including Baghdad, Aleppo, and Casablanca. People from those Jewish communities – known these days by the generalization Mizrahi – were uprooted by Muslim majorities in the mid-20th century amid rising nationalism and a backlash against Israel’s creation. Most ended up in Israel, turning the country into a more Middle Eastern place than its European Zionist founders had imagined.

The division between Jews from Europe and from the Islamic world remains one of Israel’s most painful fault lines, and it has played out in pop music. For many years, the Mizrahi sound was scorned by the curators of Israeli culture and kept on the margins. In record stores, you’d have a section for “Israeli” music, meaning mostly music by artists of European ancestry and orientation, and a separate section for “Mizrahi” or “Mediterranean” music, even though this music, too, was in Hebrew and produced in Israel. There was a time when you could barely get Mizrahi music played on the radio, and anyone who wanted to keep up with the latest hits had to go to a cluster of scruffy cassette shops around the Tel Aviv bus station. That reality was an expression of the broader disenfranchisement of Israelis from the Islamic world, who were rarely spotted in the academy or in the corridors of power.

Recent years have seen a reversal. Mizrahi music is now the country’s leading pop genre. When the daily newspaper Yediot Ahronot published a list of the most-played songs of the year in 2017, the paper’s political reporter Amihai Attali remarked on Twitter that all 15 of the artists were Mizrahi: “Anthropologically, it’s an incredible statistic,” he wrote. These days, it is Mizrahi performers who fill the biggest venues. Stalwarts of the old music scene line up for collaborations with stars such as Ms. Hadad, which would have been unthinkable 10 or 15 years ago.[…]

Not everyone loves this development, or what it signifies. Asked last month for his opinion of a different Mizrahi cover by Ms. Hadad, this one of a 1974 hit by the beloved Israeli rock band Kaveret, band member Efraim Shamir called the new version “a musical ISIS” – that is, a particularly Middle Eastern kind of desecration. He was echoing an infamous comment from Tommy Lapid, a late politician and Cabinet minister born in Yugoslavia : Asked for his take on a Mizrahi song, Mr. Lapid joked, naming a Palestinian city, that we didn’t conquer Tulkarm, Tulkarm conquered us.

The contentious politician responsible for this year’s anniversary celebrations – and for Ms. Hadad’s cover – is the Culture Minister, Miri Regev, a combative voice known for railing against the old cultural elites. Ms. Regev, who is of Moroccan descent, belongs to Benjamin Netanyahu’s Likud Party, whose political base has traditionally been heavy on Israelis with roots in the Islamic world. Ms. Regev regularly stokes nationalist sentiment and is reviled on the left; the liberal daily Haaretz has called her “Trump in high heels.”

Ms. Regev has said publicly that Arabic music “has something to offer Israeli culture,” and, in her post at the Culture Ministry, has made it her business to push the Middle Eastern sound to center stage. Last year’s Independence Day celebration starred Nasreen Qadri, a popular performer in the Mizrahi genre who is Arab – something that did not seem to happen under culture ministers from the left, who might have wanted a peace agreement with the Arab world but did not think much of Arab culture, or of the Israeli Jews who share that culture. It is a useful lesson for anyone who believes that Israel’s politics can be easily understood or categorized.

The rise of the Middle Eastern sound, impossible to ignore on this anniversary, shows how the margins here have moved to the centre. Ms. Hadad’s new Mizrahi cover of a classic about rainy Europe was akin to the planting of a flag, a way of saying, This country is mine, and so is this song.