Laszek jestem ja poganin,

Wszyscy mnie tu mają za nic,

Poga-poga-poganiają mną....

A ła łałł!

A ja zasie, miły draniu,

Mam ich w d-dużym p-powazianiu,

W du-du-d-du-du...w

dużym powazianiu ich mam....

A ła łałł!

Z przodu ja mam winkiel czerwony,

Z tyłu ziółty—ten!—

sraken-kreuz!

Muzulman, muzulman,

W morde bym ci dał:

Kippy zbierasz pan!

Muzulman, muzulman,

Kopnięć mało, duzo chleba,

Ze sie zezryć ani nie da.

Hei-li, hei-li, esiu-esiu!

Trajluj dalli führu-esiu....

Boże, czyż mi źle?!

Cholera, psiakrew

Na mego vorarbeitra!

Niech go ma krew zaleje dziś!

Muzulman, muzulman,

Jakiś wielki pan,

Jakiś wielki pan.

Za drutami słońce świeci,

Za drutami skaczą dzieci,

A na drutach czarny, smutny trup....

U-u uuu...

Cienki jestem, cieniuteńki

I lekutki, głupiusieńki,

W brzuchu burczą puste flaki—tu

U-u uuu!

Może jesteś ty Italiano,

Może Iwan lub Mojsie ty?

Muzulman, muzulman!

Bracie, pyska daj—

B r a c i e biedny mój.

Muzulman, muzulman,

Oczy gasną, wargi sine,

Z dziecka—popiół! ...Boga nie ma!

Hopaj-siupaj, połamańcze,

J-jupaj-siupaj! Jo se tańce!

Rzygam ciepłą krwią.

Patrzycie na mnie,

Patrzycie ludzie—

I pośród l u d z i ... podły mój skon.

Muzulman, muzulman,

Mama, moja mama,

Cicho umrzeć daj.

Wszyscy mnie tu mają za nic,

Poga-poga-poganiają mną....

A ła łałł!

A ja zasie, miły draniu,

Mam ich w d-dużym p-powazianiu,

W du-du-d-du-du...w

dużym powazianiu ich mam....

A ła łałł!

Z przodu ja mam winkiel czerwony,

Z tyłu ziółty—ten!—

sraken-kreuz!

Muzulman, muzulman,

W morde bym ci dał:

Kippy zbierasz pan!

Muzulman, muzulman,

Kopnięć mało, duzo chleba,

Ze sie zezryć ani nie da.

Hei-li, hei-li, esiu-esiu!

Trajluj dalli führu-esiu....

Boże, czyż mi źle?!

Cholera, psiakrew

Na mego vorarbeitra!

Niech go ma krew zaleje dziś!

Muzulman, muzulman,

Jakiś wielki pan,

Jakiś wielki pan.

Za drutami słońce świeci,

Za drutami skaczą dzieci,

A na drutach czarny, smutny trup....

U-u uuu...

Cienki jestem, cieniuteńki

I lekutki, głupiusieńki,

W brzuchu burczą puste flaki—tu

U-u uuu!

Może jesteś ty Italiano,

Może Iwan lub Mojsie ty?

Muzulman, muzulman!

Bracie, pyska daj—

B r a c i e biedny mój.

Muzulman, muzulman,

Oczy gasną, wargi sine,

Z dziecka—popiół! ...Boga nie ma!

Hopaj-siupaj, połamańcze,

J-jupaj-siupaj! Jo se tańce!

Rzygam ciepłą krwią.

Patrzycie na mnie,

Patrzycie ludzie—

I pośród l u d z i ... podły mój skon.

Muzulman, muzulman,

Mama, moja mama,

Cicho umrzeć daj.

Contributed by Riccardo Venturi - 2014/1/30 - 11:28

Language: English

Muselmann - Butt Collector

La versione inglese dal Libretto dell'album

English translation from the Album booklet

La versione inglese dal Libretto dell'album

English translation from the Album booklet

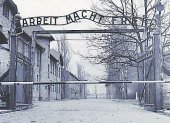

L'edificio di ingresso al lager di Sachsenhausen-Oranienburg. The building at entrance of the Sachsenhausen-Oranienburg concentration camp.

MUSELMANN - BUTT COLLECTOR

I’m a God-forsaken Polish pagan,

To everyone here I’m less than nothing,

They pu- pu- pu- push me around....

Ow-ow-oww!

But little stinker that I am,

I don’t give a da...ng about them.

I don’t give a d- d- da...ng

about them at all

Ow-ow-oww!

In front I wear a red triangle patch,

On my backside—ptui!—

a yellow shit-caked swastika!

Muselmann, Muselmann,

I’d like to slap you in the snout,

Mr. Butt Collector!

Muselmann, Muselmann,

Not too many kicks, and lots of bread—

So much, it all can’t be forced down.

Heil! Oh, heil, my li’l SS-man!

Tra-la, taradiddle, li’l Führer!

I ask you, God: Have I got it so bad?!

Hell and damnation—

Curses on my foreman!

May my blood this day spill over him!

Muselmann, Muselmann,

What a lordly sir,

What a lordly sir.

Beyond barbed wire the sun shines brightly,

Beyond barbed wire children play,

But on the barbed wire

a sad, charred body droops....

Oo-woo-woo!

I’m so thin, so very trim,

So light, so slight, so empty-headed,

Belly empty—guts are growling, too.

Oo-woo-woo!

Could you be an “Italiano”?

Or are you “Ivan”? Maybe “Moishe”?

Muselmann, Muselmann!

Brother, let me kiss your snout,

BROTHER, my poor brother!

Muselmann, Muselmann,

Eyes grow dull, lips grow cold,

A child turned into a pile of ashes!

There is no God!

Hop, Hop! Hi-ho! Twisted thing!

Yippee, yahoo! Look I’m dancing!

I’m vomiting warm blood.

And you’re watching me,

Watching me, people—

Amid HUMAN BEINGS, I die my horrid death.

Muselmann, Muselmann,

Mama, my mama,

Let me die in peace.

I’m a God-forsaken Polish pagan,

To everyone here I’m less than nothing,

They pu- pu- pu- push me around....

Ow-ow-oww!

But little stinker that I am,

I don’t give a da...ng about them.

I don’t give a d- d- da...ng

about them at all

Ow-ow-oww!

In front I wear a red triangle patch,

On my backside—ptui!—

a yellow shit-caked swastika!

Muselmann, Muselmann,

I’d like to slap you in the snout,

Mr. Butt Collector!

Muselmann, Muselmann,

Not too many kicks, and lots of bread—

So much, it all can’t be forced down.

Heil! Oh, heil, my li’l SS-man!

Tra-la, taradiddle, li’l Führer!

I ask you, God: Have I got it so bad?!

Hell and damnation—

Curses on my foreman!

May my blood this day spill over him!

Muselmann, Muselmann,

What a lordly sir,

What a lordly sir.

Beyond barbed wire the sun shines brightly,

Beyond barbed wire children play,

But on the barbed wire

a sad, charred body droops....

Oo-woo-woo!

I’m so thin, so very trim,

So light, so slight, so empty-headed,

Belly empty—guts are growling, too.

Oo-woo-woo!

Could you be an “Italiano”?

Or are you “Ivan”? Maybe “Moishe”?

Muselmann, Muselmann!

Brother, let me kiss your snout,

BROTHER, my poor brother!

Muselmann, Muselmann,

Eyes grow dull, lips grow cold,

A child turned into a pile of ashes!

There is no God!

Hop, Hop! Hi-ho! Twisted thing!

Yippee, yahoo! Look I’m dancing!

I’m vomiting warm blood.

And you’re watching me,

Watching me, people—

Amid HUMAN BEINGS, I die my horrid death.

Muselmann, Muselmann,

Mama, my mama,

Let me die in peace.

Contributed by Riccardo Venturi - 2014/1/30 - 11:56

Language: Italian (Laziale Romanesco)

Traduzione di Riccardo Venturi

3 febbraio 2014

3 febbraio 2014

Per questa e per tutte le altre traduzioni vale il principio che ho proceduto dalla traduzione inglese; ovviamente, se Krzysiek Wrona vorrà metterci le mani, sarà sempre il benvenuto. Per la traduzione, vista la natura del testo ho usato una specie di romanesco di maniera. Del tutto arbitrariamente, ma servirà forse a riprodurre un po' l'andamento del testo. [RV]

MUSELMANN IL CICCAIOLO

So' un pagano polacco scordato da Dio,

Pe' tutti, qui, so' meno che gnente,

E me càcceno vi-vi-vi-via...

Ahò...!

Ma visto che so' un fetente,

De quelli nun me ne frega gnente.

Nun me ne frega un cazzo

De loro tutti quanti so',

Ahò...!

M'hanno appiccicato davanti un triangolo rosso

e de dietro, je possino!,

una svastica gialla de mmerda!

Muselmann, Muselmann,

me piacerebbe dàtte un papagno sur muso,

signor ciccaiolo!

Muselmann, Muselmann,

Nun tanti carci e un sacco de pane,

ma così tanto da nun mandallo ggiù.

Heil! Heil, heil, caro er mi' esse-esse!

Trallallero trallallà, caro er mi' fiùrer!

Dio, te domando: me so' ridotto così ?!?

Ma va' all'inferno!

Stronzo d'un caposquadra!

Che er mi' sangue je se versi addosso!

Muselmann, Muselmann,

che compìto gentiluomo,

che compìto gentiluomo.

De là dar filo spinato splende er sole,

De là dar filo spinato giòcheno li pupetti,

Ma là sur filo spinato

ce stà un cadavere afflosciato,

triste e tutto abbruciato...

Ahò...!

So' pelle e ossa, tutto azzimato,

Magro, leggero e ciò la testa vòta,

la pancia vòta, me bròntoleno le bbudella...

Ahò...!

Ahò.....!!

Ma tu sei un italiano....?

O sei Ivan? O Mosè...?

Muselmann, Muselmann!

Fratello, fàtte bacià sur muso!

Fratello, povero fratello mio!

Muselmann, Muselmann,

L'occhi s'abbàcchieno, li labbri se gèleno,

un bimbo stà incenerito!

Dio nun ce stà!

Opplà, opplà, me giro e me rigiro!

Yuhùù! Ahò guarda come ballo!

Sto a vomità sangue cardo.

E voi me state a guardà,

me state a guardà, gente:

e tra la gente fo 'na morte schifosa.

Muselmann, Muselmann,

mamma! Oh, mamma mia!

Lassateme crepà in pace.

So' un pagano polacco scordato da Dio,

Pe' tutti, qui, so' meno che gnente,

E me càcceno vi-vi-vi-via...

Ahò...!

Ma visto che so' un fetente,

De quelli nun me ne frega gnente.

Nun me ne frega un cazzo

De loro tutti quanti so',

Ahò...!

M'hanno appiccicato davanti un triangolo rosso

e de dietro, je possino!,

una svastica gialla de mmerda!

Muselmann, Muselmann,

me piacerebbe dàtte un papagno sur muso,

signor ciccaiolo!

Muselmann, Muselmann,

Nun tanti carci e un sacco de pane,

ma così tanto da nun mandallo ggiù.

Heil! Heil, heil, caro er mi' esse-esse!

Trallallero trallallà, caro er mi' fiùrer!

Dio, te domando: me so' ridotto così ?!?

Ma va' all'inferno!

Stronzo d'un caposquadra!

Che er mi' sangue je se versi addosso!

Muselmann, Muselmann,

che compìto gentiluomo,

che compìto gentiluomo.

De là dar filo spinato splende er sole,

De là dar filo spinato giòcheno li pupetti,

Ma là sur filo spinato

ce stà un cadavere afflosciato,

triste e tutto abbruciato...

Ahò...!

So' pelle e ossa, tutto azzimato,

Magro, leggero e ciò la testa vòta,

la pancia vòta, me bròntoleno le bbudella...

Ahò...!

Ahò.....!!

Ma tu sei un italiano....?

O sei Ivan? O Mosè...?

Muselmann, Muselmann!

Fratello, fàtte bacià sur muso!

Fratello, povero fratello mio!

Muselmann, Muselmann,

L'occhi s'abbàcchieno, li labbri se gèleno,

un bimbo stà incenerito!

Dio nun ce stà!

Opplà, opplà, me giro e me rigiro!

Yuhùù! Ahò guarda come ballo!

Sto a vomità sangue cardo.

E voi me state a guardà,

me state a guardà, gente:

e tra la gente fo 'na morte schifosa.

Muselmann, Muselmann,

mamma! Oh, mamma mia!

Lassateme crepà in pace.

×

![]()

Note for non-Italian users: Sorry, though the interface of this website is translated into English, most commentaries and biographies are in Italian and/or in other languages like French, German, Spanish, Russian etc.

Lyrics: Aleskander Kulisiewicz

Music: Menashe Oppenheim (“Zulejka,” 1936)

Sachsenhausen, 1940

Testo: Aleksander Kulisiewicz

Musica: Menashe Oppenheim ("Zulejka", 1936)

”Kippenstecher” (o “Kippensammler”: ciccaiolo, raccoglitore di cicche), di Wiktor Simiński. La figura al centro dice: “Dicono che 'Arbeit macht frei'? Meraviglioso! Noi lo facciamo!!!” Didascalia a sinistra: “Libero commercio”. Il prigioniero a sinistra: “Dammi del pane”; quello a destra: “Dammi delle sigarette”. Didascalia a destra: “Fabbrica di sigarette”. USHMM, Fondo Kulisiewicz.

Aleksander Kulisiewicz joined a traveling circus in the summer of 1939 and toured the Polish provinces as a clown. In his act, he would lie dead-still on the sawdust, and as the band struck up the pseudo-oriental tune “Shanghai” another clown would pummel him with an outsized rubber hammer. The circus atmo-sphere, with its raucous music and mock brutality, made a profound impression on him: Later, in 1940, when in Sachsenhausen I once again put on a “clown’s costume”—this time a tragic version of it—I was obsessed with that circus song. I thought to myself, the camp is some sort of dark, perverted circus of sadists and miscreants. But here they don’t hit you with inflated rubber clubs. Fellow prisoners looked like striped clowns on whom an entire menagerie was unleashed. There was no sawdust, only cold dirt. No one had to pretend to be dead. Kulisiewicz fixed on the haunting “Shanghai” melody for his first song creation at Sachsenhausen, “Muselmann,” inspired by an encounter with a Muselmann, an emaciated inmate who had lost the will to live. (The word, in German, means “Muslim,” and its use in camp jargon evoked the “otherness” and otherworldliness of prisoners nearing death by starvation.) First performed in July 1940 in a private concert in Cell Block 65, “Muselmann” was revised and expanded in 1943, after the arrival in Sachsenhausen of several hundred Italian prisoners. This is the version Kulisiewicz sings here. The circus melody known to Kulisiewicz as “Shanghai” originated from a Yiddish “foxtrot orientale” known as “Zulejka,” which was also known in a Polish version. Note to Polish readers: In “Muzulman” and certain other Sachsenhausen songs, Kulisiewicz intentionally employs dialect instead of literary Polish. The lyrics reproduced throughout this book preserve the author’s original spelling.

Wiktor Simiński (1897–1974), whose illustrations accompany several songs in this album, was arrested by the Gestapo in September 1939 and deported to Sachsenhausen in early 1940. A gifted amateur artist, he created more than 100 drawings, watercolors, and hand-carved artifacts in the camp, and soon after the war began painting scenes relating to his imprisonment. Simiński maintained a close friendship with fellow inmate Aleksander Kulisiewicz, with whom he planned a publication devoted to art in Sachsenhausen.

Aleksander Kulisiewicz si unì a un circo viaggiante nell'estate del 1939, e fece il giro delle province polacche facendo il clown. Nel suo numero, giaceva stecchito a terra su della segatura, e mentre il gruppo musicale suonava il motivo orientaleggiante “Shanghai”, un altro clown lo bastonava con un randello di gommapiuma di dimensioni spropositate. L'atmosfera del circo, con la sua musica aspra e i suoi scherzi brutali, fece una profonda impressione a Kulisiewicz: “Più tardi, nel 1940, quando già ero a Sachsenhausen, mi rimisi un costume da clown, ma stavolta una sua versione tragica. Ero ossessionato da quella canzone da circo. Pensavo a quel che ero: il lager è una specie di circo cupo e perverso di sadici e miscredenti. Però, qui, non ti picchiano coi bastoni di gommapiuma. I compagni di prigionia sembravano dei pagliacci vestiti a strisce, sui quali si scatenva un'intero serraglio; ma non c'era segatura, soltanto gelido sudiciume. Nessuno doveva fingere di essere morto. Per la prima canzone che scrisse a Sachsenhausen, Kulisiewicz si “fissò” con la toccante melodia di “Shanghai”. “Muselmann” gli fu ispirata dal suo incontro con un “musulmano”, un prigioniero emaciato che aveva perso ogni voglia di vivere: la parola “Muselmann” significa “musulmano” in tedesco, ma nel gergo del campo veniva applicata prigionieri che stavano per morire di fame, per sottolineare la loro condizione di esseri vicini oramai all'aldilà. La canzone fu eseguita per la prima volta nel luglio del 1940 in un concerto privato tenuto nel Blocco 65 del lager; “Muselmann” fu poi rivista e ampliata nel 1943, dopo l'arrivo a Sachsenhausen di parecchie centinaia di prigionieri italiani. Si tratta della versione qui presentata, dove gli italiani sono nominati. La melodia circense nota a Kulisiewicz come “Shanghai” derivava in realtà da un “foxtrot orientale” yiddish, noto come “Zulejka” e che aveva anche una versione polacca. In “Muzulman”, così come in altre canzoni di Sachsenhausen, Kulisiewicz usa di proposito un polacco dialettale al posto di quello letterario. In questa ed in altre canzoni si conserva l'ortografia originale dell'autore.

Wiktor Simiński (1897-1974), le cui illustrazioni accompagnano parecchie canzoni di questo album, fu arrestato dalla Gestapo nel settembre del 1939 e deportato a Sachsenhausen all'inizio del 1940. Era un artista dilettante di talento, e creò nel campo oltre 100 disegni, acquerelli e incisioni ; subito dopo la fine della guerra iniziò a dipingere scene relative alla sua prigionia. Simiński mantenne sempre una stretta amicizia con Aleksander Kulisiewicz, con il quale progettò una pubblicazione dedicata all'arte a Sachsenhausen

"This compact disc focuses exclusively on Kulisiewicz’s own song repertoire from Sachsenhausen. These recordings, preserved on reel-to-reel tapes by Kulisiewicz after the war, are of variable quality, reflecting the conditions in which they were produced, from home recordings to studio or concert hall productions. The selections are arranged chronologically and are intended to provide both a representative sample of Kulisiewicz’s artistic output and a sense of his personal reactions to the realities of life in a Nazi concentration camp"

1. Muzulman-Kippensammler

2. Mister C

3. Krakowiaczek 1940

4. Repeta!

5. Piosenka niezapomniana

6. Erika

7. Germania!

8. Olza

9. Czarny Böhm

10. Maminsynek w koncentraku

11. Heil, Sachsenhausen!

12. Pożegnanie Adolfa ze światem

13. Tango truponoszów

14. Sen o pokoju

15. Dicke Luft!

16. Zimno, panie!

17. Moja brama

18. Pieśń o Wandzie z Ravensbrücku

19. Czterdziestu czterech

20. Wielka wygrana!

Aleksander Kulisiewicz (1918–1982) was a law student in German-occupied Poland in October 1939 when the Gestapo arrested him for antifascist writings and sent him to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp near Berlin. A talented singer and songwriter, Kulisiewicz composed 54 songs during five years of imprisonment. After liberation, he remembered his songs as well as ones he had learned from fellow prisoners and dictated hundreds of pages of them to his nurse in a Polish infirmary. As a “camp troubadour,” Kulisiewicz favored broadsides—songs of attack whose aggressive language and macabre imagery mirrored his grotesque circumstances. But his repertoire also included ballads that often evoked his native Poland with nostalgia and patriotic zeal. His songs, performed at secret gatherings, helped inmates cope with their hunger and despair, raised morale, and sustained hope of survival. Beyond this spiritual and psychological importance, Kulisiewicz also considered the camp song to be a form of documentation. “In the camp,” he wrote, “I tried under all circumstances to create verses that would serve as direct poetical reportage. I used my memory as a living archive. Friends came to me and dictated their songs.” Haunted by sounds and images of Sachsenhausen, Kulisiewicz began amassing a private collection of music, poetry, and artwork created by camp prisoners. In the 1960s, he joined with Polish ethnographers Józef Ligęza and Jan Tacina in a project to collect written and recorded interviews with former prisoners on the subject of music in the camps. He also inaugurated a series of public recitals, radio broadcasts, and recordings featuring his repertoire of prisoners’ songs, now greatly expanded to encompass material from at least a dozen Nazi camps. Kulisiewicz’s monumental study of the cultural life of the camps and the vital role music played as a means of survival for many prisoners remained unpublished at the time of his death. The archive he created, the largest collection in existence of music composed in the camps, is now a part of the Archives of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C.

Aleksander Kulisiewicz (1918-1982) era uno studente di giurisprudenza nella Polonia sotto occupazione tedesca quando, nell'ottobre 1939, la Gestapo lo arrestò per i suoi scritti antifascisti e lo inviò al campo di concentramento di Sachsenhausen, vicino a Berlino. Kulisiewicz era un cantautore di talento: durante i suoi cinque anni di prigionia compose 54 canzoni. Dopo la liberazione si ricordò non solo delle sue canzoni, ma anche di quelle che aveva imparato dai suoi compagni di prigionia, e dettò centinaia di pagine alla sua infermiera in un ospedale polacco. In quanto “cantastorie del campo”, Kulisiewicz prediligeva le ballate descrittive, usando un linguaggio aggressivo e brutale per riprodurre le circostanze grottesche in cui si trovava assieme agli altri; ma il suo repertorio comprendeva anche ballate che, spesso, evocavano la Polonia natia con nostalgia e patriottismo. Le sue canzoni, eseguite durante riunioni segrete, aiutarono i prigionieri a far fronte alla fame e alla disperazione, sostenendo il morale e le speranze di sopravvivenza. Oltre a rivestire un'importanza spirituale e psicologica, Kulisiewicz riteneva che le canzoni del campo fossero anche una forma di documentazione. “Nel campo”, scrisse, “ho cercato sempre di creare versi che servissero da reportage poetico diretto. Ho usato la mia memoria come un archivio vivente. Gli amici venivano da me e mi recitavano le loro canzoni.” Quasi ossessionato dai suoni e dalle immagini di Sachsenhausen, Kulisiewicz cominciò a raccogliere una collezione privata di musica, poesia e opere d'arte create dai prigionieri. Negli anni '60 si unì agli etnografi polacchi Józef Ligęza a Jan Tacina in un progetto di raccolta di interviste scritte e registrate con ex prigionieri a proposito della musica nei campi di concentramento. Cominciò anche a tenere una serie di spettacoli, trasmissioni radiofoniche e incisioni del suo repertorio di canzoni di prigionia, che si ampliarono fino a comprendere materiale proveniente da almeno una dozzina di campi. L'enorme studio di Kulisiewicz sulla vita culturale nei campi e sul ruolo decisivo che la musica vi svolgeva come strumento di sopravvivenza per molti prigionieri rimase inedito fino alla sua morte. L'archivio da lui creato, la più vasta raccolta esistente di musica composta nei campi di concentramento, fa ora parte degli archivi dell'United States Holocaust Memorial Museum a Washington.