It's kind of you to ask me sir

To tell you how I spend my day

Down in a coal black tunnel sir

I hurry corves to earn my pay

The corves they're full of coal kind sir

And I push them with my hands and head

It isn't ladylike but sir

You've got to earn your daily bread

I push them with my hands and head

And so my hair gets worn away

And you see this balding patch I've got

It shames me sir and I just can't say

For a lady's hands are lily-white

But mine they're full of cuts and segs

And since I'm pushing all the time

I've great big muscles on my legs

But I try to be respectable

But sir the shame God save my soul

For I work with naked sweating men

Who curse and swear and hew the coal

And the sight the smell the sound kind sir

Not even God could sense my shame

I say my prayers but what's the use

For tomorrow will be just the same

And all the lads they laugh at me

And sir my mirror tells me why

Pale and dirty can't look nice

And it doesn't matter how I try

Great big muscles on my legs

And a balding patch upon my head

A lady sir oh no not me

I should have been a boy instead

But thank you for your deep concern

For I love your kind and your gentle heart

But this is eighteen forty-two

And you and I are miles apart

And a hundred years or more will pass

Before we're walking side by side

But please accept my grateful thanks

God bless you sir at least you tried

To tell you how I spend my day

Down in a coal black tunnel sir

I hurry corves to earn my pay

The corves they're full of coal kind sir

And I push them with my hands and head

It isn't ladylike but sir

You've got to earn your daily bread

I push them with my hands and head

And so my hair gets worn away

And you see this balding patch I've got

It shames me sir and I just can't say

For a lady's hands are lily-white

But mine they're full of cuts and segs

And since I'm pushing all the time

I've great big muscles on my legs

But I try to be respectable

But sir the shame God save my soul

For I work with naked sweating men

Who curse and swear and hew the coal

And the sight the smell the sound kind sir

Not even God could sense my shame

I say my prayers but what's the use

For tomorrow will be just the same

And all the lads they laugh at me

And sir my mirror tells me why

Pale and dirty can't look nice

And it doesn't matter how I try

Great big muscles on my legs

And a balding patch upon my head

A lady sir oh no not me

I should have been a boy instead

But thank you for your deep concern

For I love your kind and your gentle heart

But this is eighteen forty-two

And you and I are miles apart

And a hundred years or more will pass

Before we're walking side by side

But please accept my grateful thanks

God bless you sir at least you tried

Contributed by The Lone Ranger - 2010/5/13 - 14:30

La canzone Refugee dei Chumbawamba non è che un adattamento originale di "The Testimony of Patience Kershaw"...

The Lone Ranger - 2010/5/13 - 14:42

Language: Italian

Tentativo di traduzione italiana di The Lone Ranger.

LA TESTIMONIANZA DI PATIENCE KERSHAW

Sei gentile, signore, a domandarmi

Di raccontarti come trascorro le mie giornate

Giù nella galleria nero carbone, signore

Sbrigo i carichi per guadagnarmi la paga

I carrelli sono pieni di carbone, gentile signore,

E io li spingo con le mani e con la testa.

Non è un lavoro da donne ma, signore,

Bisogna guadagnarsi il pane ogni giorno.

Li spingo con le mani e con la testa

E così mi sono caduti i capelli

E si vede questa chiazza che mi è venuta.

Mi vergogno, signore, e neppure posso dire

Che per una donna le mani siano candide

Le mie sono piene di tagli ed ulcere

E da quando spingo tutto il tempo

Mi sono venute le gambe muscolose

Ma cerco di essere decente

Però, signore, che vergogna – che Dio mi salvi,

Perché lavoro con uomini tutti nudi e sudati

Che imprecano e bestemmiano mentre scavano il carbone

E quella vista, e l’odore, e il rumore, gentile signore,

Neppure Dio potrebbe immaginare la vergogna che provo.

Io lo prego ma, come sempre,

Domani sarà lo stesso.

E tutti i ragazzi ridono di me

E, signore, lo specchio mi dice perché:

Pallida e sporca come sono non posso certo sembrare carina

E non serve che ci provi

Ho questi grossi muscoli nelle gambe

E questa chiazza sulla testa.

Una signora, signore, oh, non certo io!

Avrei dovuto essere un ragazzo piuttosto.

Comunque, grazie per la tua compassione

Apprezzo la tua gentilezza ed il tuo nobile cuore

Ma è il 1842

E tu ed io siamo lontani miglia

E cento anni o forse più passeranno

Prima di camminare l’uno a fianco all’altra.

Ma, per favore, accetta il mio grazie di cuore.

Che Dio ti benedica, signore, almeno ci hai provato.

Sei gentile, signore, a domandarmi

Di raccontarti come trascorro le mie giornate

Giù nella galleria nero carbone, signore

Sbrigo i carichi per guadagnarmi la paga

I carrelli sono pieni di carbone, gentile signore,

E io li spingo con le mani e con la testa.

Non è un lavoro da donne ma, signore,

Bisogna guadagnarsi il pane ogni giorno.

Li spingo con le mani e con la testa

E così mi sono caduti i capelli

E si vede questa chiazza che mi è venuta.

Mi vergogno, signore, e neppure posso dire

Che per una donna le mani siano candide

Le mie sono piene di tagli ed ulcere

E da quando spingo tutto il tempo

Mi sono venute le gambe muscolose

Ma cerco di essere decente

Però, signore, che vergogna – che Dio mi salvi,

Perché lavoro con uomini tutti nudi e sudati

Che imprecano e bestemmiano mentre scavano il carbone

E quella vista, e l’odore, e il rumore, gentile signore,

Neppure Dio potrebbe immaginare la vergogna che provo.

Io lo prego ma, come sempre,

Domani sarà lo stesso.

E tutti i ragazzi ridono di me

E, signore, lo specchio mi dice perché:

Pallida e sporca come sono non posso certo sembrare carina

E non serve che ci provi

Ho questi grossi muscoli nelle gambe

E questa chiazza sulla testa.

Una signora, signore, oh, non certo io!

Avrei dovuto essere un ragazzo piuttosto.

Comunque, grazie per la tua compassione

Apprezzo la tua gentilezza ed il tuo nobile cuore

Ma è il 1842

E tu ed io siamo lontani miglia

E cento anni o forse più passeranno

Prima di camminare l’uno a fianco all’altra.

Ma, per favore, accetta il mio grazie di cuore.

Che Dio ti benedica, signore, almeno ci hai provato.

Contributed by The Lone Ranger - 2010/5/14 - 09:01

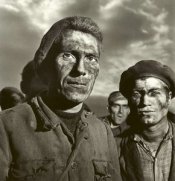

Nel 1842 la Children's Employment Commission presentò al Parlamento inglese un rapporto sulle condizioni delle donne e dei minori impiegati nelle miniere del Regno. Ragazzini e ragazzine erano all’epoca utilizzati come “hurriers”, trasportavano cioè i carrelli carichi di materiale attraverso le gallerie delle miniere, e lo facevano anche per 12 ore consecutive… delle vere, piccole bestie da soma…

A hurrier and two thrusters heaving a corf full of coal, England 1853

A hurrier and two thrusters heaving a corf full of coal, England 1853

Il Parlamento approvò subito una legge che vietava il lavoro in miniera delle donne e delle bambine, ma solo nel 1870 fu vietato anche per i bambini e, comunque, il lavoro minorile nelle miniere inglesi fu sradicato soltanto dopo il 1920.

Questa canzone è tratta direttamente da una delle testimonianze raccolte dalla commissione d’inchiesta del 1842, quella data da una “hurrier”, Patience Kershaw, di 17 anni, costretta a scendere nei pozzi del carbone alla morte del padre, che aveva lasciato moglie e 10 figli…

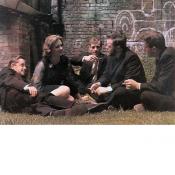

“Although written fairly recently by Frank Higgins of Liverpool this moving song is based very literally on the actual evidence given by young Patience Kershaw before the Government Commission of Enquiry into Child Labour in 1842. As a result of the enquiry in that same year an Act of Parliament prohibited the underground employment in the mines of women and boys under ten years old. (The Ian Campbell Folk Group)

“My father has been dead about a year; my mother is living and has ten children, five lads and five lasses; the oldest is about 30, the youngest is four; three lasses go to the mill; all the lads are colliers, two getters and three hurriers; one lives at home and does nothing; mother does nought but look after home.

All my sisters have been hurriers, but three went to the mill, Alice went because her legs swelled from hurrying in cold water when she was hot. I never went to day-school; I go to Sunday school, but I cannot read or write; I go to pit at 5 o'clock in the morning; I get my breakfast of porridge and milk first; I take my dinner with me, a cake, and eat it as I go; I do not stop or rest any time for the purpose; I get nothing else until I get home, and then have potatoes and meat, not every day meat. I hurry in the clothes I have now got on, trousers and ragged jacket; the bald place upon my head is made by thrusting the corves; my legs have never swelled, but sisters' did when they went to mill; I hurry the corves a mile and more under ground and back; they weigh 300 cwt [hundredweight]; I hurry 11 a-day; I wear a belt and chain at the workings to get the corves out; the getters that I work for are naked except their caps; they pull off all their clothes; I see them at work when I go up; sometimes they beat me, if I am not quick enough, with their hands; they strike me upon my back; the boys take liberties with me sometimes, they pull me about; I am the only girl in the pit; there are about 20 boys and 15 men; all the men are naked; I would rather work in mill than in coal-pit." (Patience Kershaw, minatrice di 17 anni, Halifax, West Yorkshire, Inghilterra, 1842)

A hurrier and two thrusters heaving a corf full of coal, England 1853

A hurrier and two thrusters heaving a corf full of coal, England 1853

Il Parlamento approvò subito una legge che vietava il lavoro in miniera delle donne e delle bambine, ma solo nel 1870 fu vietato anche per i bambini e, comunque, il lavoro minorile nelle miniere inglesi fu sradicato soltanto dopo il 1920.

Questa canzone è tratta direttamente da una delle testimonianze raccolte dalla commissione d’inchiesta del 1842, quella data da una “hurrier”, Patience Kershaw, di 17 anni, costretta a scendere nei pozzi del carbone alla morte del padre, che aveva lasciato moglie e 10 figli…

“Although written fairly recently by Frank Higgins of Liverpool this moving song is based very literally on the actual evidence given by young Patience Kershaw before the Government Commission of Enquiry into Child Labour in 1842. As a result of the enquiry in that same year an Act of Parliament prohibited the underground employment in the mines of women and boys under ten years old. (The Ian Campbell Folk Group)

“My father has been dead about a year; my mother is living and has ten children, five lads and five lasses; the oldest is about 30, the youngest is four; three lasses go to the mill; all the lads are colliers, two getters and three hurriers; one lives at home and does nothing; mother does nought but look after home.

All my sisters have been hurriers, but three went to the mill, Alice went because her legs swelled from hurrying in cold water when she was hot. I never went to day-school; I go to Sunday school, but I cannot read or write; I go to pit at 5 o'clock in the morning; I get my breakfast of porridge and milk first; I take my dinner with me, a cake, and eat it as I go; I do not stop or rest any time for the purpose; I get nothing else until I get home, and then have potatoes and meat, not every day meat. I hurry in the clothes I have now got on, trousers and ragged jacket; the bald place upon my head is made by thrusting the corves; my legs have never swelled, but sisters' did when they went to mill; I hurry the corves a mile and more under ground and back; they weigh 300 cwt [hundredweight]; I hurry 11 a-day; I wear a belt and chain at the workings to get the corves out; the getters that I work for are naked except their caps; they pull off all their clothes; I see them at work when I go up; sometimes they beat me, if I am not quick enough, with their hands; they strike me upon my back; the boys take liberties with me sometimes, they pull me about; I am the only girl in the pit; there are about 20 boys and 15 men; all the men are naked; I would rather work in mill than in coal-pit." (Patience Kershaw, minatrice di 17 anni, Halifax, West Yorkshire, Inghilterra, 1842)

×

![]()

Note for non-Italian users: Sorry, though the interface of this website is translated into English, most commentaries and biographies are in Italian and/or in other languages like French, German, Spanish, Russian etc.

Album “Something To Sing About”

Written by Frank Higgins

Il Parlamento approvò subito una legge che vietava il lavoro in miniera delle donne e delle bambine, ma solo nel 1870 fu vietato anche per i bambini e, comunque, il lavoro minorile nelle miniere inglesi fu sradicato soltanto dopo il 1920.

Questa canzone è tratta direttamente da una delle testimonianze raccolte dalla commissione d’inchiesta del 1842, quella data da una “hurrier”, Patience Kershaw, di 17 anni, costretta a scendere nei pozzi del carbone alla morte del padre, che aveva lasciato moglie e 10 figli…

“Although written fairly recently by Frank Higgins of Liverpool this moving song is based very literally on the actual evidence given by young Patience Kershaw before the Government Commission of Enquiry into Child Labour in 1842. As a result of the enquiry in that same year an Act of Parliament prohibited the underground employment in the mines of women and boys under ten years old. (The Ian Campbell Folk Group)

“My father has been dead about a year; my mother is living and has ten children, five lads and five lasses; the oldest is about 30, the youngest is four; three lasses go to the mill; all the lads are colliers, two getters and three hurriers; one lives at home and does nothing; mother does nought but look after home.

All my sisters have been hurriers, but three went to the mill, Alice went because her legs swelled from hurrying in cold water when she was hot. I never went to day-school; I go to Sunday school, but I cannot read or write; I go to pit at 5 o'clock in the morning; I get my breakfast of porridge and milk first; I take my dinner with me, a cake, and eat it as I go; I do not stop or rest any time for the purpose; I get nothing else until I get home, and then have potatoes and meat, not every day meat. I hurry in the clothes I have now got on, trousers and ragged jacket; the bald place upon my head is made by thrusting the corves; my legs have never swelled, but sisters' did when they went to mill; I hurry the corves a mile and more under ground and back; they weigh 300 cwt [hundredweight]; I hurry 11 a-day; I wear a belt and chain at the workings to get the corves out; the getters that I work for are naked except their caps; they pull off all their clothes; I see them at work when I go up; sometimes they beat me, if I am not quick enough, with their hands; they strike me upon my back; the boys take liberties with me sometimes, they pull me about; I am the only girl in the pit; there are about 20 boys and 15 men; all the men are naked; I would rather work in mill than in coal-pit." (Patience Kershaw, minatrice di 17 anni, Halifax, West Yorkshire, Inghilterra, 1842)